Bielorrusia es un país que está dividido casi perfectamente entre Oriente y Occidente. En la parte oriental, por un lado, Rusia conserva una fuerte influencia: el 70 % de los habitantes habla ruso en vez de bielorruso. En Occidente, por el otro, está la frontera con Polonia, Lituania y Letonia, todos países miembros de la Unión Europea. Los lazos con estos vecinos tampoco son insignificantes. Incluso en la Edad Media los duques de Lituania hablaban una variante de bielorruso antiguo.

La guerra actual al sur de Ucrania, sin embargo, ha edificado un nuevo Muro de Berlín entre Rusia y los demás países europeos. En 2015, el presidente de Bielorrusia, Alexander Lukashenko, supervisó las negociaciones de paz entre Rusia, Ucrania y la Unión Europea, en Minsk. Nadie sabe a ciencia cierta qué va a pasar en un futuro, pero es probable que Lukashenko haya perdido entusiasmo tanto en la política autoritaria soviética como en la ostentosidad rusa. Sobre todo después de ser testigo de lo que vivieron Crimea y Ucrania.

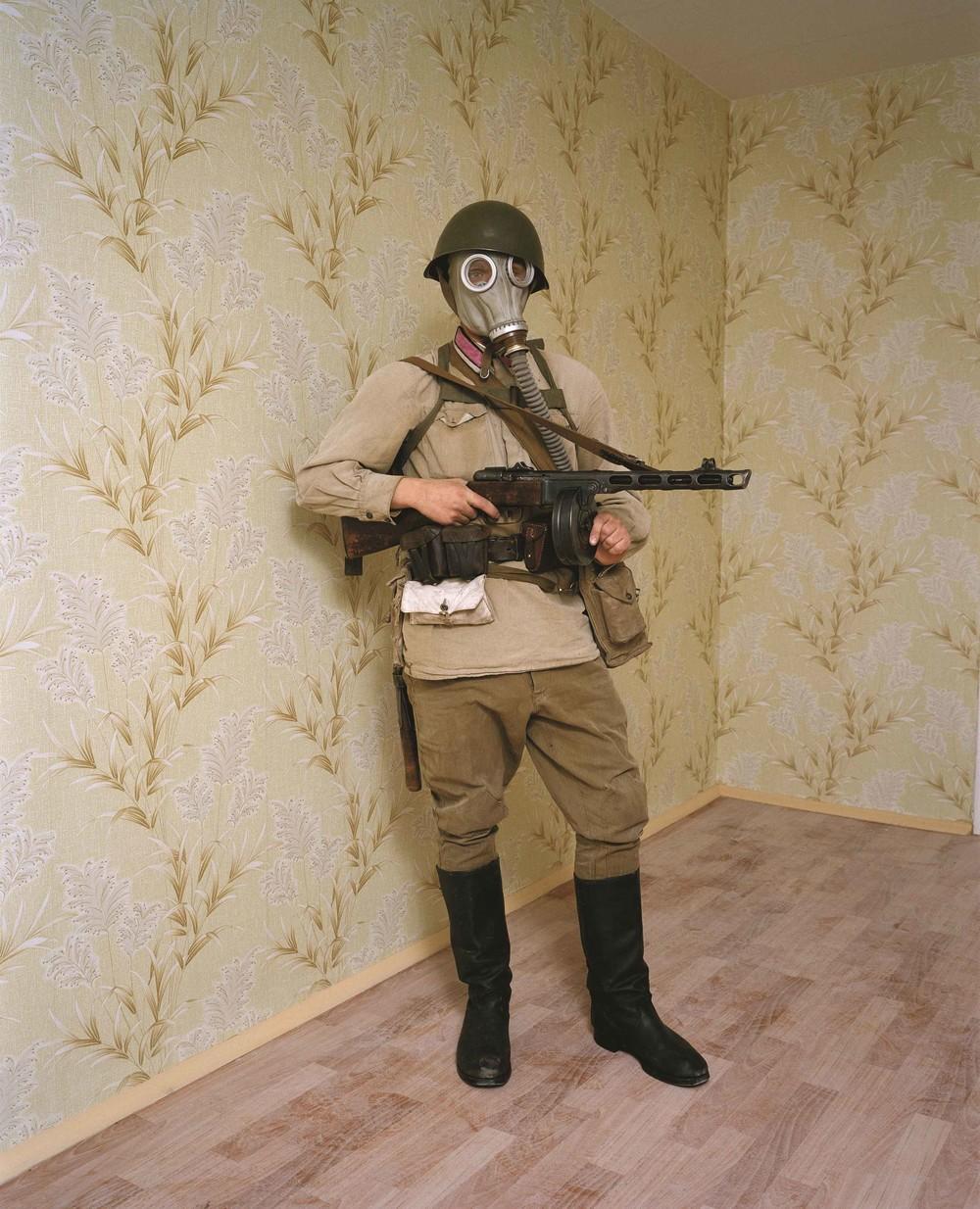

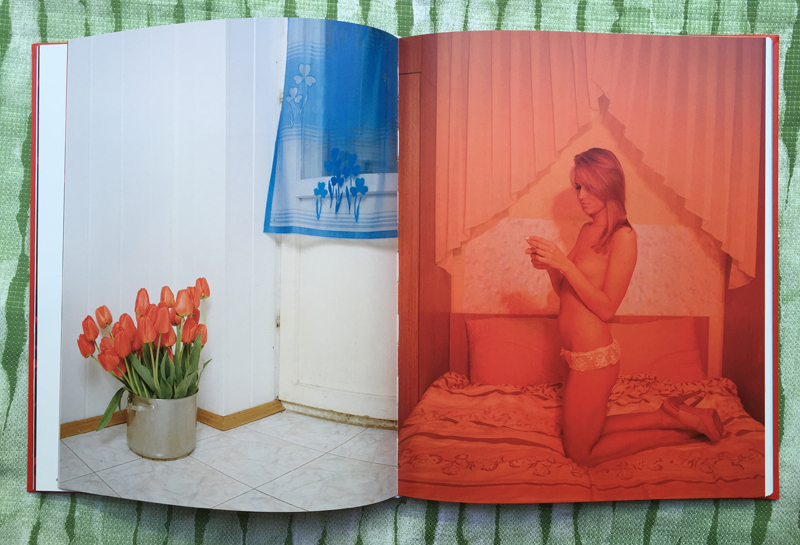

Comencé a viajar a Bielorrusia hace seis años para tomar fotos del Día de la Victoria, una fecha en la que se celebra la victoria de los soviéticos frente al fascismo de la Alemania nazi. Durante la celebración de ese día, uno puede ver tractores de artillería, tanques de guerra y trabajadores de fábricas desfilando por las calles de Minsk. Una bandera vieja de la Unión Soviética se alza a lo alto de la torre de radio de la capital. En Stalin Line, un parque de temática militar donde hay una estatua de Stalin, un grupo de hombres vestidos con uniformes soviéticos y nazis recrean las batallas de la Segunda Guerra Mundial. Los tulipanes rojos, símbolo de la primavera y el rejuvenecimiento en la Unión Soviética, inundan las calles y se entregan como regalo a los veteranos de guerra para agradecerles por sus servicios. La experiencia puede llegar a ser muy confusa: un retroceso en el tiempo. Las cicatrices y las historias de guerra se han vuelto el foco central de un gobierno en busca de una identidad nacional unificada. Pronto descubrí que en Bielorrusia también se celebran otras fiestas nacionales de Rusia, como la Revolución de Octubre y el Día de los Defensores de la Patria. Regresé año tras año al país para fotografiarlas todas. Sin embargo, los días festivos son algo más que un simple telón de fondo de mi proyecto. Las fiestas me permitieron seguir la trayectoria de la cultura nacional mientras buscaba algo más personal: una comprensión más profunda de un mundo que debería formar parte del pasado pero se empeña en adaptarse al presente.

I began my trips to Belarus about five years ago to photograph Victory Day, a holiday celebrating the Soviet victory over fascism and Nazi Germany. During the celebrations tractors, military equipment, and factory workers parade through the streets. A vintage USSR flag flies on a radio tower over the city. And red tulips, a symbol of spring and rejuvenation in the USSR, line the streets and are given to war veterans as a way of thanking them for their service. It can be disorienting and feel like you are traveling back in time to the USSR or a perfectly preserved Stalinist museum. I soon discovered that many other Soviet-style holidays like October Revolution Day and May Day are also still observed in Belarus. I returned year after year to photograph them. In a way, though, the holidays were more of a backdrop to my project, a way of following the path of official culture while looking for something more personal. I would often wander off the trail in an effort to seek more intimacy and understanding of a world that should be part of the dead USSR past, but is stubbornly resilient in the present.

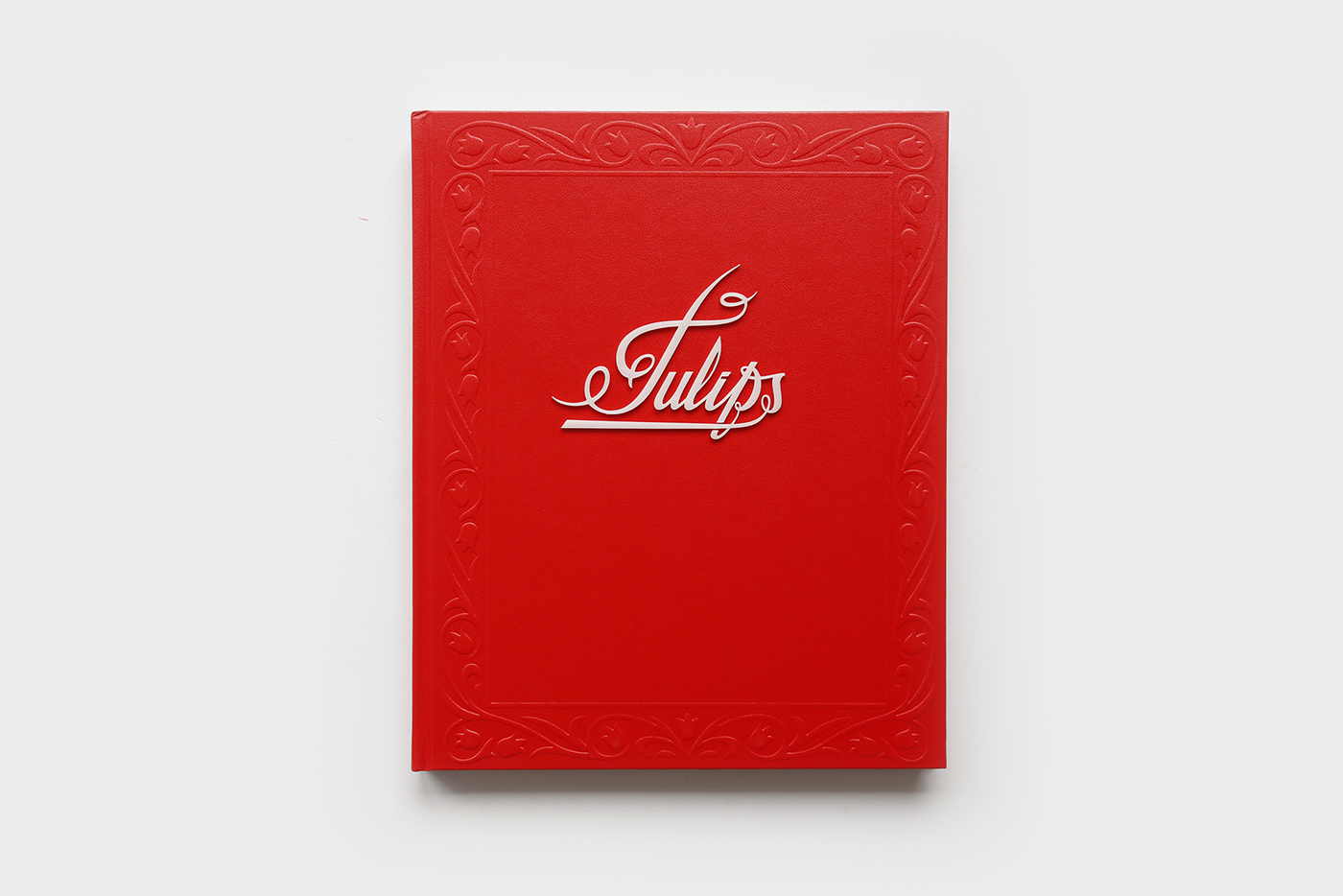

I’m now ready to publish a book of the TULIPS photographs.I will self-publish TULIPS as I did with my DISKO book that I successfully funded through Kickstarter last year.I really love the DIY -DO IT YOURSELF- approach to publishing and being able to make a book exactly how I think it should be.The resulting book is then more of an object or artwork in itself and not just a catalog of photographs.I had a lot of success with DISKO and it was featured in several magazines and on some great websites like VICE, BuzzFeed, and CBS News.