Elinor Carucci comenzó a fotografiar cuando tenía catorce años, animada por un espontáneo deseo de documentar su vida a través de una serie de imágenes más o menos congruentes. Lo hizo, además, sin ningún tipo de pretensión ni tampoco con un objetivo: años después insistiría que sólo deseaba dejar constancia de «su ser y estar» a través de imágenes simples pero nunca sencillas que contaban su adolescencia como hija de un matrimonio norteamericano corriente. Hay algo íntimo, levemente perturbador en las imágenes de la adolescente Carrucci, que logra captar el rostro envejecido y amable de su madre, las ausencias del padre, las habitaciones abiertas y cerradas de su memoria doméstica. Un pulso honesto no sólo con un lenguaje fotográfico carente de artificio sino algo mucho más profundo: una capacidad para analizar la realidad desde cierta franqueza descarnada que a la distancia, resulta incómoda.

La Elinor Carucci adulta conservó intacta esa noción sobre la sinceridad visual. De hecho, su celebrado trabajo fotográfico es una mezcla de un día a día sublimado a través de la imagen y algo mucho más complejo y cerebral. Aunque en apariencia casual y accidental, no hay nada que el ojo atento de Carucci no analice bajo la luz del discurso. Una meditada conclusión sobre la vida de su entorno inmediato y sobre todo, el poder de la fotografía para desmenuzar la realidad en fragmentos concretos de lenguaje. La obra de Carucci que abarca casi tres décadas e incluye su vida familiar en todas las facetas asombra justo por su mutabilidad, pero también, por su percepción muy directa sobre un objetivo preciso: recorrer la percepción sobre lo cotidiano como una serie de rituales y visiones personales de enorme importancia artística.

No obstante, Carucci no considera que su formidable trabajo y sus implicaciones sea mejor o más específico que la atención concreta que toda madre dedica a sus hijos. Y de allí quizás la formidable tensión visual que sostiene una obra que tiene algo de perturbador por la atención meticulosa y obsesiva a los detalles. Hace unos años, un periodista preguntó a Carucci si la fotografía le ha permitido establecer una relación peculiar o más profunda con sus hijos que otras madres. Carucci pareció desconcertada por la idea. «No creo que los retrate más que otros padres, solo que de manera distinta», contestó, «los miro como todas las madres contemplan a sus hijos, sólo que yo tengo una cámara en la mano al hacerlo».

¿Es ese elemento de profunda noción sobre sus relaciones privadas y emocionales lo que hace el trabajo de Elinor Carucci distinto? ¿O se trata de algo intangible, una insistente necesidad de traducir lo corriente y habitual en una idea mucho más sensitiva y sensible, que la fotografía refleja como herramienta artística ideal? Para Carucci la respuesta parece estar entre ambas percepciones de la imagen como medio artístico y un instrumento estético capaz de construir una percepción profunda sobre lo que el discurso fotográfico puede ser. Carucci madre pero también fotógrafo, crea un recurso capaz de traducir las infinitas variaciones del día a día íntimo en un planteamiento elemental. La cámara como reflejo. La cámara como puerta a una idea profunda sobre su propia identidad.

Una y otra vez: las infinitas variaciones de la individualidad

Para Carucci, la fotografía es mucho más que un medio expresivo. Es una reflexión sobre todos los aspectos de su vida y sobre todo, la capacidad del arte para sostener un punto de vista novedoso sobre lo habitual. Quizás por ese motivo y con su marido como cómplice, ha retratado cada aspecto de la vida de sus hijos desde el nacimiento hasta la adolescencia con una frecuencia y una persistencia que transforma el documento visual en algo más que un simple registro fotográfico. Desde discusiones y peleas entre los niños, hasta momentos de intimidad tan profunda que han llevado a una agria discusión sobre su responsabilidad sobre la imagen de sus hijos, Carucci combina su obra artística con una visión antropológica de profunda belleza e importancia conceptual. Para la fotógrafa, el acto de fotografiar se ha convertido en algo más que una ejecución concreta sino más bien, en un diálogo argumental con su entorno. Y de allí su triunfo, su relevancia y sobre todo, trascendencia. Para Carucci, el objeto fotográfico su familia, su vida, las relaciones y vínculos invisibles que les unen se sostienen sobre esa percepción suya sobre la imagen que transforma y elabora una puntual expresión sobre la individualidad.

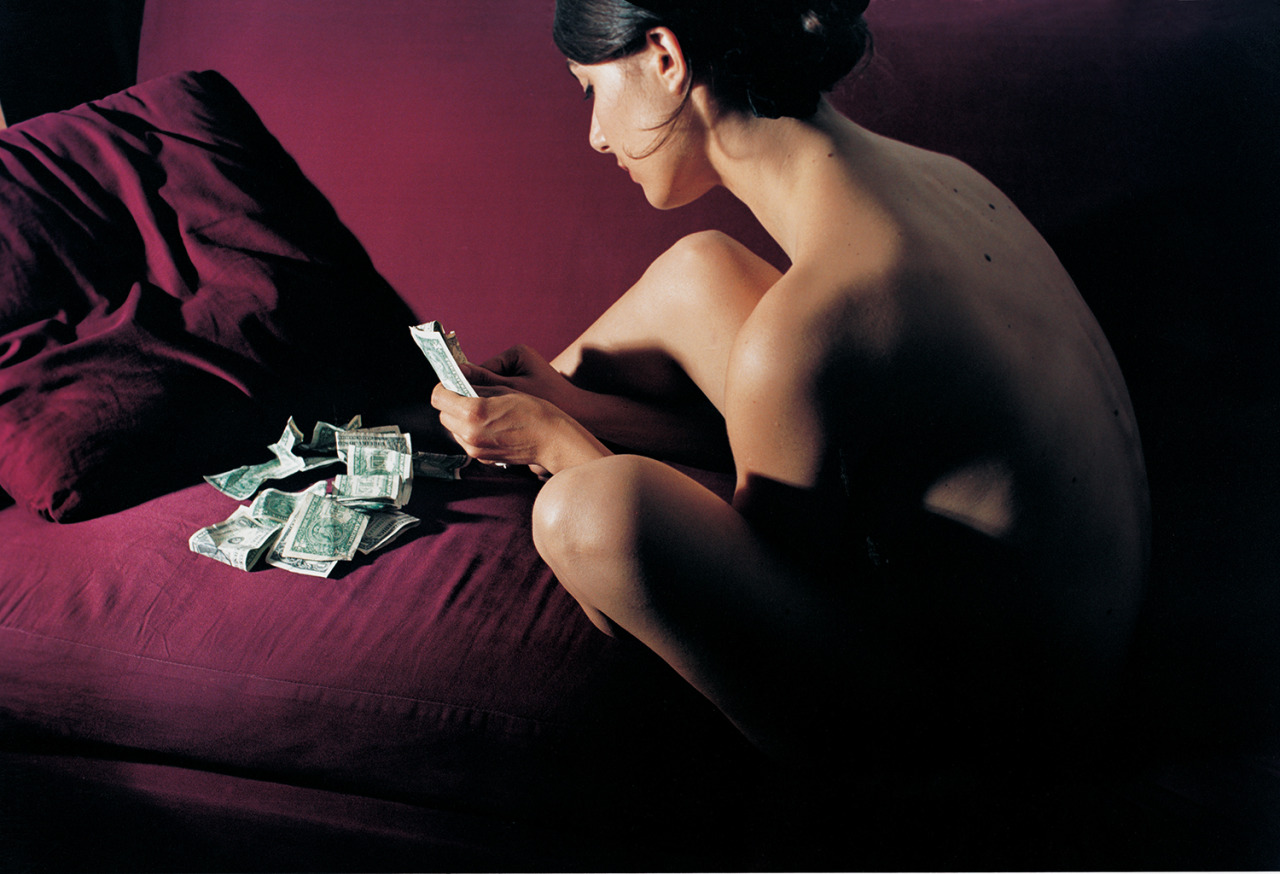

Quizás por ese motivo, tiene tanto valor la interrelación no sólo emocional que Carucci sostiene con su familia: hay un elemento sensible y conmovedor en cada una de sus fotografías, incluso las que han sido juzgadas directamente pornográficas y sometidas al escrutinio público desde su capacidad para escandalizar. Carucci, que no se atiene a las reglas comunes de la fotografía familiar, transgrede de manera consciente líneas y dimensiones del pudor que convierten al grueso de su obra en un manifiesto de idea específico que puede resultar desagradable en lo esencial. Después de todo, pocas veces lo íntimo se muestra tan visible, tan descarnado, con una percepción casi cruda de su cualidad anecdótica. Carucci lo hace y además, avanza más allá para hacerse preguntas existenciales y metódicas sobre todo tipo de reflexiones sobre lo que somos más allá de la mirada pública. Las infinitas variaciones personales y abstractas sobre lo que nos define como individuo. Para Carucci, la fotografía familiar un término falso y blando que no logra definir medianamente su trabajo es algo orgánico y poderoso que subvierte el orden de la noción sobre lo público y lo privado. Lo problematiza a un nuevo nivel que además, analiza la visión de lo humano y lo humanístico a través de trozos de información sabiamente construidos para analizar una perspectiva común. La fotógrafa no intenta responder preguntas, sino plantear posibilidades sobre la convivencia en común, la percepción de los paisajes íntimos y sobre todo, analizar el trasfondo de la identidad compartida como un todo emocional que desborda la percepción del yo.

Elinor Carucci y los pequeños símbolos femeninos trascendentes

En el libro recopilatorio del trabajo de Elinor Carucci titulado Madre, una de las fotografías la muestra desnuda, amamantando a la vez a sus gemelos recién nacidos. No es una fotografía utópica de la maternidad sino algo más doloroso, real y tangencial. Carucci tiene un aspecto casi clásico, en un juego de luz y sombra natural que la muestra hermosa pero también agotada, frustrada y cansada. Sostiene un bebé en cada mano y parece luchar contra la resistencia de los bebés a mamar de sus pechos desnudos. La fotografía causó revuelo por su franqueza y abrió de nuevo una encendida discusión sobre la llamada «pornografía» cotidiana en el trabajo de la fotógrafa. Artículos y ensayos se preguntaron si su búsqueda del realismo no llevaba a cierta provocación implícita e incluso un crítico la acuso de forzar la relación de los símbolos visuales hacia algo más grotesco que el mero documento, en busca de una polémica artificial.

Eso, a pesar que las imágenes son algo más que la desnudez de las madres y de los bebés. Que el elemento realmente perturbador reside no en el hecho de mostrar lo evidente en este caso a la madre desnuda y un acto de suprema intimidad como lo es amamantar sino hacerlo de manera cruda, sin búsqueda directa de la belleza ni tampoco de cierta armonía o justificación. La fotografía muestra a la maternidad desde un punto de vista que pocas veces se toca: desde el miedo hasta la incomodidad. Una angustia invisible que convierte a la madre no sólo en un mero objeto simbólico y que podría calzar en cualquier estereotipo visual previo sino en un registro poderoso sobre la emoción. Con esa pequeña reflexión sobre el dolor real, la incomodidad y cierta angustia existencial, la fotógrafa lleva el documento a otro nivel, lo transforma en algo mucho más ambiguo y poderoso. Retrotrae el poder de la imagen como expresión visual de ideas conjuntivas hacia algo más vital y sincero que cualquier otra fotografía al uso.

Como suele ocurrir, Carucci se negó a responder de manera directa a la acusaciones y al escándalo que propició la fotografía. De hecho, nunca lo ha hecho, ni antes y después. Con su mirada inquebrantable que intenta comprender la vida en todas sus vicisitudes, se limitó a seguir fotografiando. «Los gemelos tienen nueve años ahora. Los he fotografiado continuamente», dijo en una entrevista posterior. «Es en parte porque eso es lo que hago. No puedo dejar de ser un fotógrafo. Veo el mundo a través de una lente. Es cómo lo entiendo. Pero también es más que eso: pensé que convertirme en una madre cambiaría quién soy y que quería reflejar eso. Las cosas cambian, no sólo nuestros cuerpos. Hay algo que nos une a todos en madres que se convierten. No es la Madonna puramente beatífica y el Niño. Espero que cada una de mis fotografías refleje una universalidad».

Quizás en esa salvedad la profundidad temática y el alcance del trabajo de Carucci, resida su contundencia. Ninguna de sus fotografías se limita a analizar los espacios emocionales y temporales al uso. Lo hace con una belleza en ocasiones agresiva que conmociona por su realismo emotivo. Los temores, las preocupaciones, las lágrimas, el amor y la risa se transforman no sólo en temas fotográficos sino también, en una cuidadosa combinación de reflexiones e interpretaciones sobre lo que la fotografía puede ser como medio de un discurso más poderoso que lo obvio. En el trabajo de Carucci todo versa sobre un sentido de la identidad, el espacio y el lugar de enorme importancia. Carucci recurre su mundo el privado y el que habita más allá y recopila imágenes que transforma en un lenguaje consecuente. Una reflexión sobre la vida real que nadie muestra o mejor dicho, que nadie desea mostrar. Por compleja, por dolorosa, por incómoda e incluso, sólo por desagradable. Es justo en esa grieta sobre la posibilidad de mostrar o no hacerlo lo que permite al Carucci encontrar una identidad nueva en un tipo de imágenes sino también, algo más sencillo y poderoso. Una vitalidad asombrosa que hace de su trabajo y propuesta un documento desbordante de pura belleza real.

De todas las facetas de la realidad: El escenario de la propia vida

En el 2012 Elinor Carucci ganó la beca Guggenheim, gracias a su trabajo Diary of a Dancer, en la que contó a través de imágenes su vida como bailarina en Nueva York. La cámara la siguió con un pulso obsesivo hacia el escenario, revelando lo bello y lo feo de una faceta artística la mayoría de las veces malinterpretada y en ocasiones, subestimada. En la serie abunda la intimidad, pero también una intimidad profunda y bien asimilada, creada a base de escenas en alta velocidad, autorretratos tomados con cronómetro y pequeños detalles de cada aspecto de su cotidiano. Elinor acababa de emigrar desde su natal Israel y el choque étnico y cultural también en notorio en sus fotografías. «Me sentí como inmigrante cuando llegué aquí y, hasta cierto punto, todavía lo hago», confesó en una entrevista posterior. «Yo estaba rodeado de mi propia cultura y familia, hablando hebreo, y entonces… era tan extraño. El proyecto de baile era mi manera de mostrarlo, pero creo que también estaba usando las fotografías para ayudarme a entenderlo».

No obstante, fue con el proyecto Madre que Elinor Carucci alcanzó el reconocimiento internacional y cultural. Y lo hizo a través del mismo método que Diary of a Dancer, pero llevado a otra expresión y a otro nivel. La búsqueda de intimidad llega a un dimensión inédita y lo hace con un golpe de efecto maravillosamente calculado: Hay fotografías de sus hijos llorando y no se trata de imágenes idílicas y suavizadas para el consumo. En todas ellas pueden verse ríos de moco saliendo de su nariz. Hay escenas de los niños golpeando, gritando, saltando, abrazados durmiendo juntos. Una y otra vez la imagen de la belleza idílica se rompe bajo el peso de una ternura dolorosa y rica en matices.

A Carucci se le ha acusado de todo, desde pornógrafa hasta veladas acusaciones de abuso infantil debido a sus fotografías. Pero ellas las ignora todas. Unos años atrás y durante la gira de publicación del libro Madre resumió no sólo lo esencial de su trabajo sino también, la forma como intenta interpretarlo como parte de una idea artística. «Mi objetivo es capturar lo cotidiano con todo el dolor y las dificultades, así como el amor y la alegría. No puedo limitarme a lo que es apetecible y lo que no es o de lo contrario las imágenes no funcionan. La vida es dolorosa y desagradable y quizás allí radica su magia». Una mirada poderosa sobre los mínimos secretos de lo cotidiano y más allá de eso, la belleza que nace de lo dolorosamente real.

ENG: The process of taking photographs in her new country began only when she started documenting her own immigrant experience, working as a belly dancer at parties and functions across the city. «I had to find a personal point of view,» she says. The result, Diary of a Dancer, shows her travelling on the subway in her bellydancing regalia, applying her make-up in bleak washrooms, whirling across dancefloors before a jubilant crowd. Naturally, the process of simultaneously dancing and photographing proved problematic. «I tried different things, like asking strangers to take the photographs, and it didn’t work,» she says. «So I asked my husband, Eran, to help. And he really doesn’t like weddings.»

Eran Bendheim, also a photographer, accompanied her to some performances. «It started with me being very controlling because I was afraid it won’t be my photograph,» Carucci says. «I was like, ‘Stand here, and when I make a sign … ‘» She soon realised that her interference was proving detrimental. «Bellydancing – it’s not like the New York City Ballet, when you know what you’re going to do with it. I could be at the other end of the room, or on the table. We couldn’t plan it. He had to follow me round and take pictures so I said, ‘OK, so some of it will be your work.'» Bendheim’s work, much, it seems, like his temperament, is starkly different from Carucci’s. «He photographs black and white in the street,» she says. «And his work deals with urban landscape, people being alienated, not being connected to one another, and mine is about connecting.”

Carucci took up photography aged 15. She had tried theatre and playing the saxophone, but this was the first thing that rang true. «I know the difference between having to do something, and wanting to do something,» she says, «and photography … I just loved it.» For the next nine years she was rarely without a camera, capturing her immediate family at such close range, and in such exceptionally personal situations, that one wonders whether they found the camera intrusive. «No,» says Carucci. «I started so young, and it was nine years between me starting to take photos and them being shown, so it gave us a lot of time to get used to it without involving the exposure part.» The «exposure part» came in her degree show, and in a collection of photographs titled Closer, that reveal everything from her grandfather in the shower to her parents in their underwear, via the imprint a zip has left on skin.

Her family, she adds, are granted approval before the pictures are exhibited. Occasionally they will veto a picture. «My father doesn’t care,» she says. «I mean, he has his limits; he doesn’t want to be photographed nude. But my mum … I can’t describe the pictures she wouldn’t let me show because she’ll kill me. It’s not like a photograph of her naked in the middle of the room, it’s just something about how she looks, like a wrinkle or something, or she says, ‘My hair looks so bad!’ But that’s how I learned – she has to feel comfortable too, and if she feels more comfortable changing what she’s wearing or putting on make-up, I have to respect that.»

Though many of her pictures are staged, Carucci’s work somehow retains an intense spontaneity. «I learned that it doesn’t matter if images are staged or not. It doesn’t make them more or less truthful. We make unconscious decisions about how we want to be photographed.» She sometimes looks at her self-portraits and sees «that I presented something that is very true. And usually the ones that don’t work, it’s because they’re not honest; the light is beautiful, the colours are beautiful, but they’re not honest.»

Indeed, it is an unflinching honesty that characterises Carucci’s work, and much of that honesty appears to manifest itself in her predilection for photographing her subjects in a state of undress. This was not, she stresses, an altogether conscious decision. «I guess it’s a combination of the way I was at home – the way my mom or dad would walk around in their underwear, or after their bath naked. It’s not like we’re living our lives naked, it’s just before the shower, where I can walk into the bathroom in my underwear and ask my father something. It’s so, so normal and I thought that most families are like that. I realised only after I took those images how unusual it is, because of how shocked people were by my photographs. I realise that some of my pictures were more provocative – like me and my father naked. Even for us, that was a bit weird. But images of me and my mum naked? I’m like, ‘What’s the big deal? You’ve never seen your mum naked?’ And many people said no. I was really surprised.»

She did not set out to be provocative, but did realise that some pictures might nudge certain taboos. «My father is a man and my brother is a man, and there are tensions underneath that we don’t even dare to think about. I wanted to photograph that it could be so everyday but it could still have this tension or awkwardness.» And occasionally taking the photographs proved a little strange. «Once the camera is there, they become weird moments. If I’m naked, no one pays much attention. But if I bring the camera, everyone is much more aware.”

She began photographing Bendheim a year into their relationship, that first photograph documenting a fight between them. He, too, was relaxed about being photographed unclothed. «When I met Eran, he was actually more of a nudist than me,» she laughs. «He was naked all the time! He photographed himself naked. He comes from a family of photographers, he’s so knowledgeable about photography and wants to help me and he can be naked all day … so I thought, ‘This is the man for me!'»

Perhaps Carucci’s most emotionally revealing photographs come in a series named Crisis, which records a difficult spell in her relationship with Bendheim. What is most surprising is that her husband allowed her to record their rows. «Yes,» she says, «this is extraordinary for me. Because we were going through the worst time. We’d been together since ’93. We went through a lot. We left our country and we moved here. We were immigrants together. That time was really bad. I had back pain and I was depressed and there was another man involved in my life and Eran lost his job and I think I was so down that I couldn’t dance, I couldn’t perform, and I think I really had to take pictures. It really helped me. I felt like me again. And then I started taking pictures of us, and I think it was one of the things that brought us back together.

«I was even shocked by myself, taking the camera out. I’m not an aggressive person, and at the time I was also … not afraid of Eran, but there was this tension. And he let me take the photograph, which I was moved by. He didn’t say no. And then also many times we had a horrible day and I would take the tripod to make a self-portrait and he would come suddenly and touch me. And I thought, what was that all about? It was something he did not for the camera, but for me to see, to show that this is what he wants the picture to be about. So I think it helped me understand, and helped him understand, that simple fact that we still loved each other despite all the anger and all that was happening.»

She tells the story with the same glad honesty that characterises her pictures. The first image in the series she titled And If I Don’t Get Enough Attention, which shows her naked and staring straight at the camera, lying on top of a sleeping Eran, whose clothes almost blend in with the dark blue sofa. «This,» she says, «was the first image where I knew I was thinking about our situation, and I knew that I was thinking of things that were happening to me that he didn’t know. The camera at the time knew more than my husband.»

Now Carucci is documenting the lives of her young twins. She photographed her pregnancy and their birth, but the task is proving increasingly difficult. «Now they’ve begun to crawl,» she laughs. «So I can’t have lights up or a camera with a tripod. I have to develop different ways of photographing.» She has set up spotlights to help her, and is improvising new ways of using the flash. «But for a while I could only photograph them with my cellphone. I’m actually thinking about exhibiting some of them.» Beyond this, the direction of her work remains, even to her, a glorious mystery: «The photography follows my life,» she says. «Life comes first. And wherever my life takes me, I will photograph it».

Elinor Carucci | Por Aglaia Berlutti & by Laura Barton