YO SIEMPRE HABÍA SENTIDO QUE EN ALGÚN LUGAR DE LAS PROFUNDIDADES DE MI FOTOGRAFÍA TENÍA QUE HABER UNA CONEXIÓN CON LA VIDA Y LA MUERTE … Y, SIN EMBARGO, INCONSCIENTEMENTE, HABÍA DECIDIDO NO TOCARLO DIRECTAMENTE.

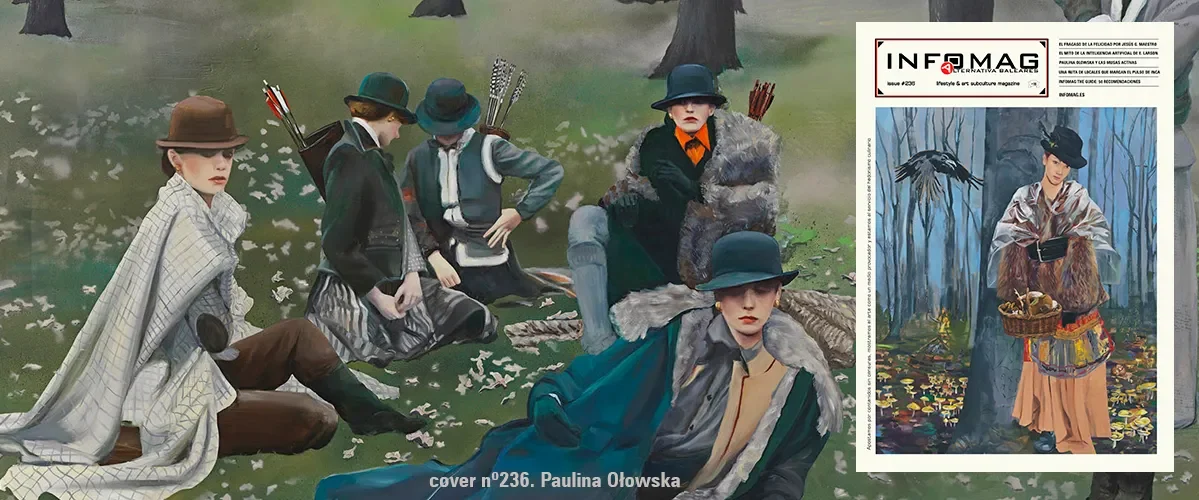

Lieko Shiga es una fotógrafo japonesa (nacida en la prefectura de Aichi en 1980) que realiza fotografía altamente creativa. Tras estudiar fotografía de una forma muy reglada y orientada al blanco y negro clásico en Japón, tuvo que salir a respirar nuevas formas de fotografía 5 años a Londres. Allí se graduó en 2004 en la Chelsea University of Art and Design con un BA en Fine Art New Media, pero ya antes había expuesto en solitario en Osaka, Japón, Floating Occurrence en 2001 y Jaques saw mw tomorrow morning en 2003.

Su limitada habilidad en Inglés y la falta de dinero para materiales le condujo hacia un enfoque introvertido y a diseñar sus propias técnicas. Inicialmente utilizaba las impresiones más baratas, que cortaba y perforaba, luego los retroiluminaba para la luz brillara a través de los agujeros, y luego fotografiaba de nuevo. Aunque su técnica ha evolucionado, su enfoque conceptual se mantiene constante: para ella, las fotografías son la suma de las experiencias que la llevaron a un lugar, a un sitio donde se escenifica un escenario.

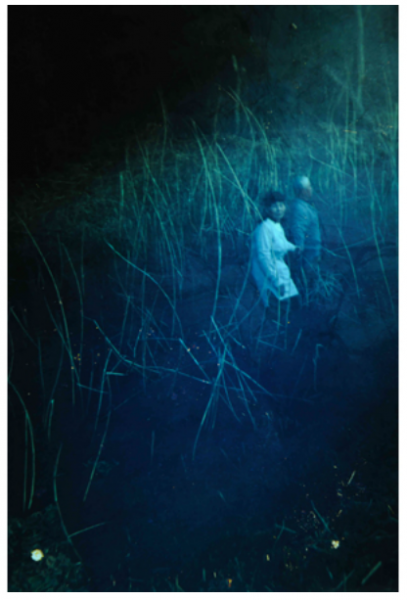

Sus espeluznantes imágenes de su serie Lilly consiguen crear una sensación irreal de estar en los espectadores. Con la inspiración de las populares fotografías paranormales de los primeros tiempos de la fotografía, Lieko obtuvo estas imágenes de residentes de un bloque de viviendas municipales en el este de Londres, donde ella estaba estudiando.

Canary es una secuencia cuidadosamente editada de diapositivas de fotografías fijas, proyectadas en una pared y acompañadas por una banda sonora ambiental. Las fotografías fueron tomadas por Shiga durante sus residencias en Brisbane y Sendai en 2006, y se convirtió en una obra proyectada para exposiciones en Australia y Sendai a finales de 2006. (por Luis Martínez Aniesa)

ENG: Lieko Shiga has become the rising star of Japanese photography by employing a completely different style to everybody’s favourite Japanese photographer, Rinko Kawauchi. Whereas Kawauchi is serene and understated in her approach, Shiga is flamboyant and expressionist, unafraid to deploy every technical trick in the book, using both the documentary and the staged photograph approaches. Her imagery does not so much display a style as flaunt a sensibility. And that sensibility is poetic, ebullient, and endlessly inventive, certainly not that of a shrinking violet. She first came to attention with her book Lagoon in 2008, and now looks set to cement her reputation with her new, ambitious project, Spiral Coast.

The Spiral Coast project (which currently stands at three books) derives from the period, beginning in 2008, when Shiga went to live in the small community of Kitakama, in Japan’s Miyagi Prefecture. She was invited to become the village photographer, which meant recording the religious festivals and other community events marking the year’s passage. Kitakama lies in an area of sand dunes and pine trees, designated by Shiga as the ‘Spiral Coast’, and these became a great inspiration for her work, although nature was to prove problematic. The area was badly hit by the earthquake and tsunami of 2011. Shiga lost her studio and many images she had made of the community. Far worse, Kitakama lost some sixty souls out of the 107 families residing there, and the village was flattened.

SPIRAL COAST/album might therefore be said to perform a memorialising function, although that is to simplify what is an extremely complex work. Frequently, photography is an act of claiming and holding on to something memories, evidence, relationships, the world. Here, the medium certainly does seem to fulfil that brief, although in this case it is an act of reclamation an act of remembrance and reflection before life inevitably carries on. Shiga does this in an extremely proactive way; this is no passive process. She does not so much record the world as remake it. She does not so much fabricate photographs as inhabit them. From this one might gather that Shiga is no realist photographer. The other two books that comprise the Spiral Coast project deal more directly with the community of Kitakam, but the ‘trippy’ album (to use the Sixties vernacular) is the most personal, the poetic flight of fancy. And it certainly is a dark poetry. Shiga’s images seem to be taken mainly in the gloaming, and the whole ambient feeling is one of darkness and uncertainty. Nothing is what it seems. Many of the pictures are dark, murky even. Shiga likes to shoot at night with a flash that doesn’t quite cover the frame, producing an unsettling vignetting effect. So in many of the pictures the image seems only half there fugitive, tantalisingly ineffable like a vague memory.

The book is full of phantasms and shadows, from the flickering, poignant images of damaged snapshots rescued from the flood to the references – in flowers and funerals to the uncertainty of life – exemplified in a repeated image of a washed-up corpse on the beach. Yet, amidst this gloom, there is also a strangely ecstatic element. Shiga is almost as much land artist or sculptor as photographer, and one of the book’s central metaphors is where she takes a pine branch and by sweeping makes spiral and other patterns in the sand, which may echo the meditative function, and the daily sweeping of the famous Zen garden of Ryan-ji in Kyoto.

Like many significant photobooks, SPIRAL COAST/album seems as much about the photographer’s relationship with photography as her relationship with the world. It seems that Shiga is not so much utilising photography to examine her relationship with the world, but rather using the world to explore her relationship with photography. Although of course she cares for the world and in particular the community of Kitakama. Yet her imagery’s singularity and flamboyance makes her one of the most expressionist photographers I have seen, and that makes me uncomfortable with them (in a good way), as I am not normally well disposed towards pictorialism, and Shiga’s work at root is a kind of contemporary pictorialism.

One of photography’s challenges is that it deals with the literal, the material. If you want to use the medium to talk about things you cannot see in the world, like feelings, relationships, or memories, you have to find a way of bending it – usually by employing, to paraphrase Walker Evans, “not only metaphor and symbol, but paradox and play and oxymoron.”

Shiga does this by constructing not only a dense and elliptical narrative, full of blind alleys, repetition, and doubling back, but also a panoply of formal photographic strategies – ranging from the semi-abstraction of the distressed snapshots, painted and drawn over photographs, double exposures, and cross processing to create strange colour distortions. Hardly one photograph is like another, but this remarkable book is held together by Shiga’s singular sensibility – elegiac, meditative, gloomy, playful, and ecstatic by turns. The result is a gigantic, ambitious, mood piece, but a very superior if somewhat baffling one.

All images courtesy of the artist. © Lieko Shiga