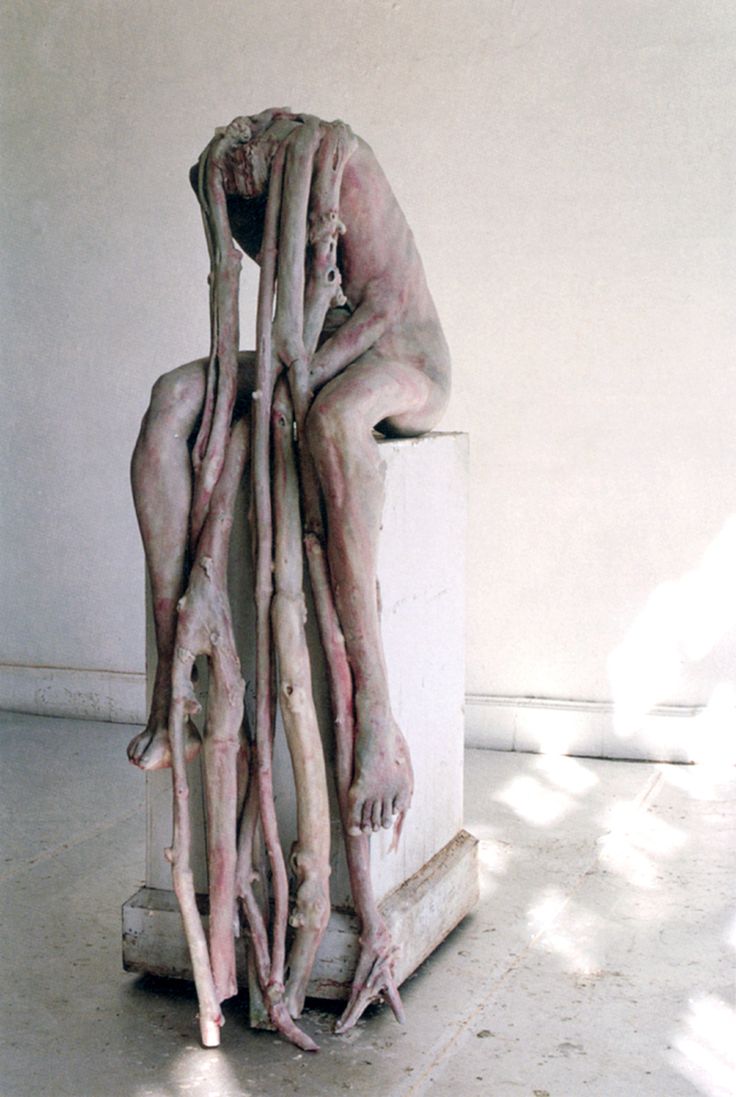

Para algunos una grotesca reinterpretación del cuerpo y para otros, en cambio, un elegante acercamiento a la transmutación de la forma; lo cierto es que es casi imposible practicar la indiferencia frente a la obra de Berlinde De Bruyckere.

¿Conoces la obra de Berlinde De Bruyckere? Para algunos, su arte podría rozar lo grotesco; para otros, se trata de una forma de lirismo matérico, una poética de la deformación. Pero más allá de la dicotomía entre repulsión y fascinación, lo cierto es que su obra se presenta como una confrontación radical con la percepción que tenemos del cuerpo.

La escultora belga subvierte nuestros códigos visuales y simbólicos, desafiando el imaginario colectivo que convierte al cuerpo humano en un campo reconocible, estable y ordenado.

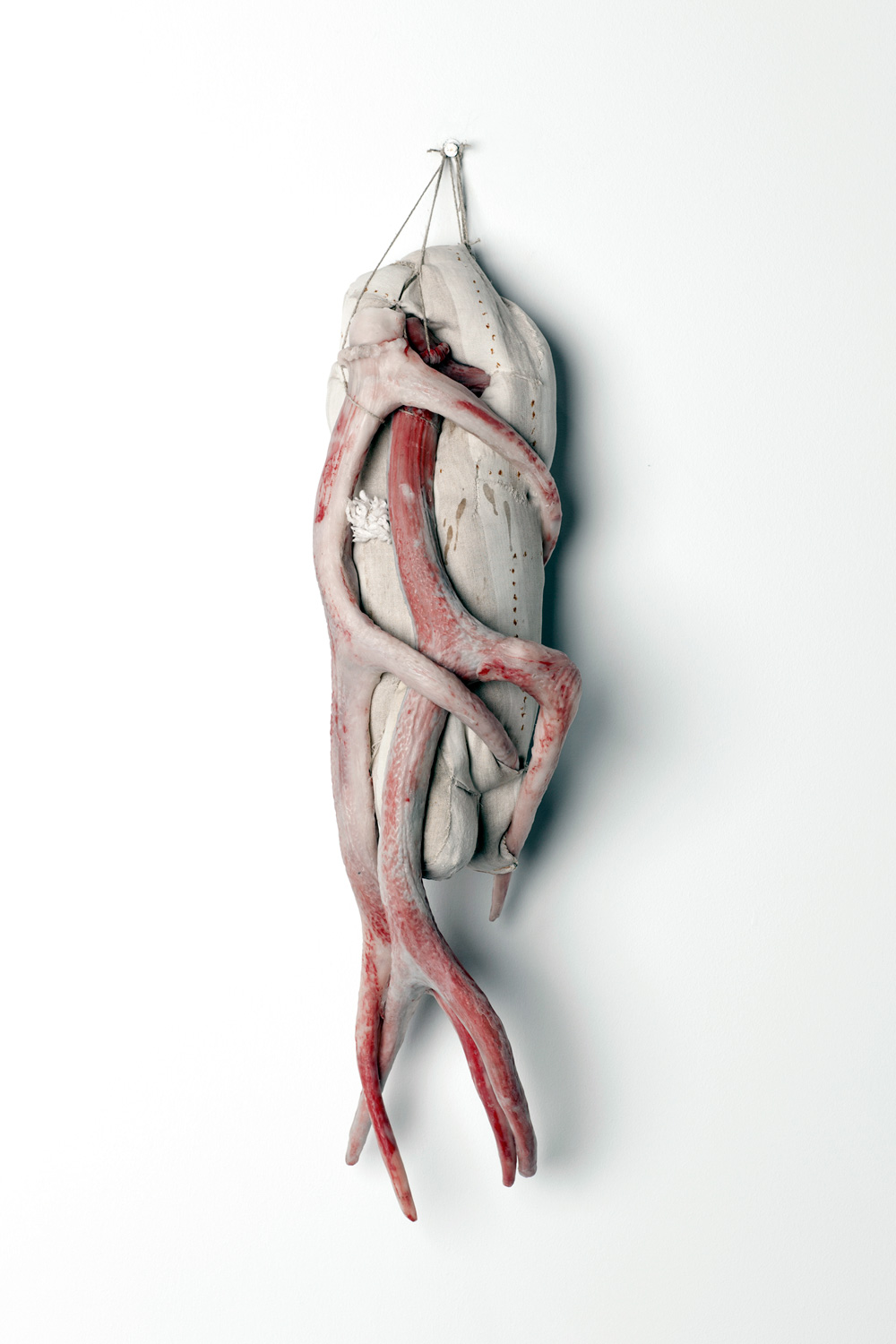

En sus esculturas —construidas a menudo con cera, madera, textiles y crines de caballo—, la forma humana se repliega sobre sí misma, se desdibuja, se replantea. La figura ya no es ni femenina ni masculina, ni siquiera del todo humana: es un residuo de humanidad, una huella corporal que existe en tensión permanente con la idea de belleza, de simetría, de funcionalidad. De Bruyckere no busca representar, sino evocar; sus cuerpos son paisajes emocionales, espacios donde la fragilidad, la violencia y la compasión coexisten sin jerarquía.

Su estética visceral no es gratuita. Al contrario, es el resultado de un pensamiento profundo sobre la condición contemporánea del ser humano, atrapado entre la pulsión de la carne y la necesidad de sentido. En esta transfiguración constante de la materia, el cuerpo ya no es símbolo, sino síntoma. Un síntoma que nos obliga a mirarnos sin filtros.

El rostro ausente y la identidad desplazada

Uno de los elementos más inquietantes en la obra de Berlinde De Bruyckere es la omisión sistemática del rostro. En el arte occidental, el rostro ha sido tradicionalmente el espejo del alma, el lugar donde se proyecta la subjetividad, la emoción, el carácter. Al eliminar esta dimensión, De Bruyckere priva al espectador de cualquier posibilidad de empatía inmediata, obligándolo a enfrentarse al cuerpo como una entidad en sí misma, sin relato, sin contexto, sin nombre.

La ausencia facial no es una carencia sino una declaración. En un mundo saturado de imágenes, de selfies, de narrativas identitarias hiperdefinidas, la artista propone una suspensión del yo. La identidad, entendida como un constructo visual y corporal, se disuelve en favor de una corporalidad ambigua, inacabada, doliente. Al borrar los puntos de anclaje de nuestra percepción —el rostro y los genitales—, De Bruyckere nos enfrenta a una desnudez radical, no solo física sino existencial.

Así, sus figuras devienen cuerpos sin biografía, sin género, sin lenguaje. Pero no por ello vacíos, sino más bien saturados de una emocionalidad muda, densa, que se transmite a través de la textura, del gesto contenido, del pliegue. Son cuerpos que no cuentan historias, pero que las cargan todas.

Hacia una estética de la asexualidad.

Otro de los pilares conceptuales de esta poética corporal es la asexualidad. En una era donde la identidad de género y la sexualidad se han convertido en terrenos de exploración y reivindicación política, De Bruyckere opta por una vía distinta: despojar al cuerpo de toda marca sexual reconocible. Esta estrategia no pretende negar la importancia del género, sino cuestionar el lugar central que ocupa la diferencia sexual en la construcción de la subjetividad.

Al eliminar los órganos sexuales, De Bruyckere no niega la corporeidad, sino que la libera. Nos recuerda que el cuerpo no es únicamente una herramienta de identificación o una zona de deseo, sino también un espacio de sufrimiento, de tránsito, de transformación.

La suya es una propuesta radicalmente inclusiva, precisamente porque no propone modelos, sino preguntas. ¿Qué es un cuerpo cuando se le priva de sus coordenadas simbólicas más evidentes? ¿Qué queda de nosotros cuando se desactiva el mapa de signos que nos hace legibles para los demás?

En este contexto, su obra puede leerse como una meditación filosófica sobre el límite entre lo humano y lo informe, entre el dolor y la redención, entre lo visible y lo que se resiste a ser dicho. Su discurso es inquietante porque toca una fibra profunda: aquella que nos recuerda que, tras todas las capas culturales, seguimos siendo cuerpos en lucha. Cuerpos que sangran, que mutan, que envejecen, que anhelan, pero que, ante todo, son.

Para más información: Berlinde De Bruyckere

¿Conoces la obra de Berlinde De Bruyckere? Por Mónica Cascanueces.