«Sobre todo es una exposición enorme», dice esta artista que precisa tener mucha obra más allá de la fotografía y de lo ahora expuesto, sobre el tema «autorretrato de la imagen» en un sentido muy amplio. Recalca que las imágenes no son de gran formato, pues para lo que quiere transmitir con ese trabajo no necesita en absoluto hacer fotos grandes, ni quiere que sean más grandes que el tamaño normal de su cabeza normal. Interesada en el tiempo que pasa y en captar lo único que se ve de él, «las huellas que deja, en mi cuerpo, en mi cara, o en la de cualquier persona», Ferrer recuerda que «no sabemos lo que es el tiempo» y que es imposible de atrapar. Resalta, al respecto, que comenzó a utilizarse como modelo «desesperada» al no encontrar amigos y conocidos que se dejasen fotografiar, y al no querer recurrir a profesionales, porque «en la época era caro», y por querer trabajar sobre «un cuerpo de todos los días, que va a trabajar, se levanta…», pero sin ser censurada. «Esa fue la manera de poder hacer siempre lo que quería cuando quería», apunta Ferrer, que inicio sus retratos del tiempo «primero con el sexo y la cabeza», luego, poco a poco, con las otras partes. Mantiene que «no era audaz en absoluto» y que «todo el mundo lo hacía», en aquella época del movimiento de liberación de las mujeres, cuando tantas artistas querían «dar una imagen de la mujer diferente de la que la historia del arte ha dado desde hace siglos». Residente en París desde hace décadas, Ferrer calcula que desde hace unos 20 años vive de su arte, tras haberse ganado la vida como traductora, periodista y de otras maneras, costeando siempre ella misma su trabajo artístico. «Por eso he tenido toda la libertad del mundo», añade Ferrer, a quien no le gusta exponer y, «en consecuencia», ha vendido poco. Del arte, resalta: «lo único que me interesa verdaderamente es hacerlo. Todo lo demás, lo hago porque lo tengo que hacer». «Mi única obligación con el arte es hacer lo que yo quiero hacer de la manera mejor posible», luego que cada cual interprete y diga lo que quiera, afirma Ferrer, ajena a las críticas «porque somos todos muy diversos».

ENG: What’s happened to the rock stars of performance art, the ones who were the celebrities of art and feminism in the ’70s? Well, they’ve got old, just like everyone else. But this doesn’t mean that they’ve holed themselves up in their flats with five cats -some of them, like the 77- year-old Esther Ferrer, are still filming and photographing themselves, studying the transformations happening to their faces and their aging bodies. The life of an artist therefore becomes the performance itself: a work that is destined to fade slowly over the years.

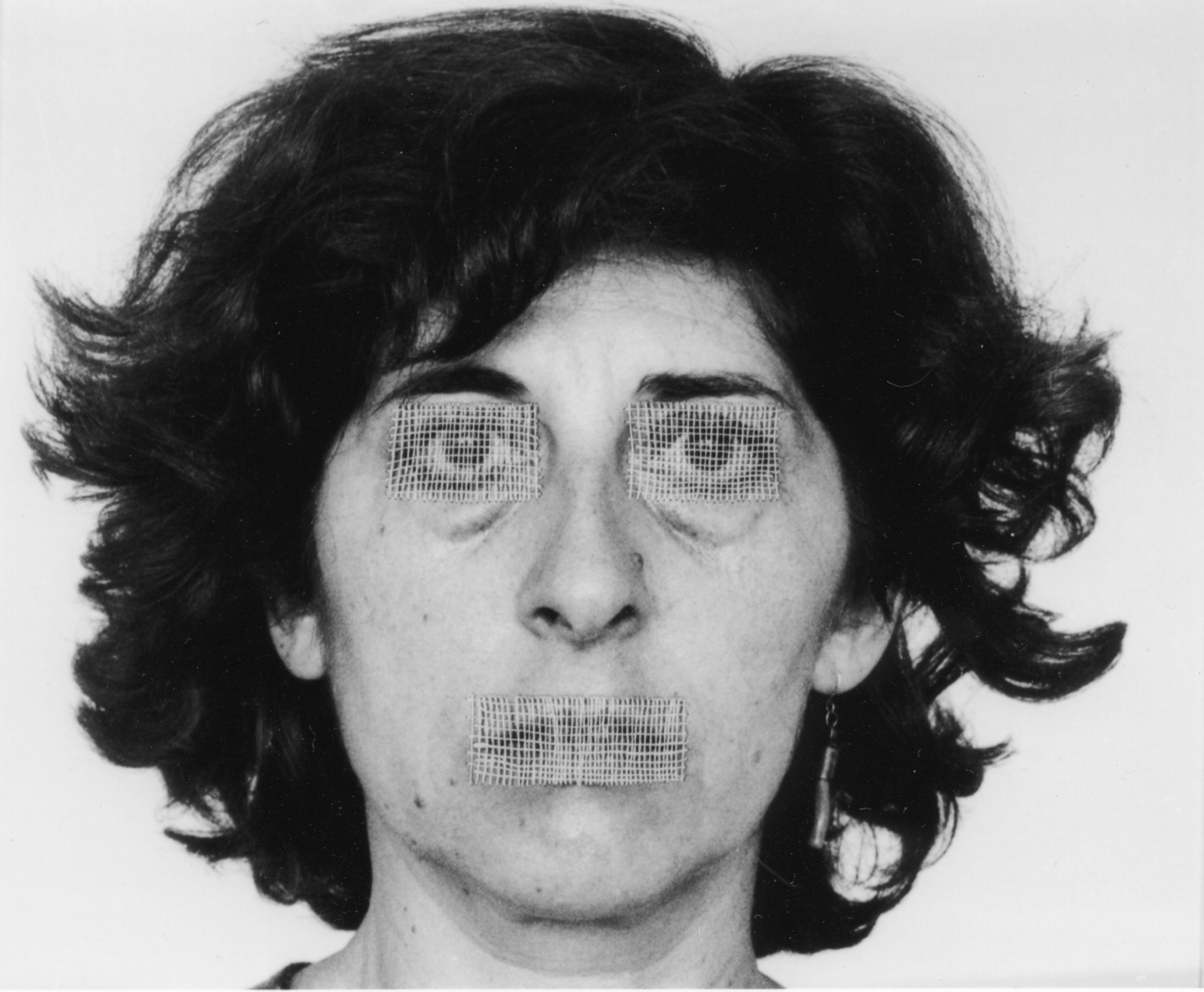

Over the years, Basque performance artist Esther Ferrer has occupied the same space in the art world as Marina Abramovic and Valie Export (although her art doesn’t reach quite the same masochistic extremes). As one of the pioneers of ‘action art’, her body is the central motif her videos, photomontages and installations hail from another era, pre-Photoshop, pre-abortion and pre-Femen, and have to be understood as such. This is someone who prints her face on the concertina of an accordion just in order to disfigure it as much as possible, who photographs her pubic hair and then colours it red, yellow, green and blue, who lines up dozens of self-portraits on a wall, increasing the exposure of each photo little by little until the last one is nothing more than empty white space. Examining the finite nature of life and the constant transformation of the body has added more depth to her work with age. In particular in the huge frieze of ‘double faces’ photographs where the artist combines self-portraits taken at different stages of her life (1981, 1989, 1994, 1999, 2004, 2009, 2014) into one picture.

Without embarrassment and without a value judgement, Ferrer is the heroine of a passive performance: not direct action, but the observation of her own transformation, over which she has no control.